About 10 years ago, I sat down with my wife and my brother to watch David Lynch’s 1980 masterpiece, The Elephant Man. At the time, this was one of the only Lynch movies that I hadn’t seen, and I was excited to watch a new-to-me Lynch. As an avid fan of his, I found that I had reserved some of his movies “to watch later,” because I found it comforting to know that there were still works that I hadn’t seen. But, with Season 3 of Twin Peaks having been announced, the fact of so much new material in the pipeline pushed me to catch up on whatever I’d missed.

So, I poured a bourbon and sat down to watch Lynch’s second feature, and first major production. As the movie began with a series of surreal images depicting African elephants seemingly attacking a woman, fading in and out between the woman and the animals in slow motion as she screams, and then slowly focusing on a darkened room, filled with smoke, and the sounds of a crying baby telling the viewer that the woman was pregnant during the attack, I felt right at home in the mind of David Lynch. Even as the narrative became more linear, those initial images and sounds hovered over the film like a miasma.

But something strange happened as the movie continued, something I didn’t expect. I kept thinking about my mom. Something within this tragic story of deformity and societal cruelty put my mom into my mind and I couldn’t get her out. While The Elephant Man is certainly an emotional film, I felt something break open within myself as I watched it that seemed to come from someplace other than the movie itself.

The fact that I thought about my mom during a movie was not, at that time, in itself a strange occurrence, because she had unexpectedly died just a few months beforehand at the age of 55 of “accidental Oxycodone toxicity.” Supposedly it is a peaceful death. Her brain was swollen, which, from what I’ve read, indicates that she would have felt relaxed and increasingly sleepy. She went to bed and never got back up. She did love sleeping in.

We discovered her death because my wife, Ashley, my brother, Sam, and I went to her apartment to check in on her after she went some days without returning our phone calls or messages online. While it wasn’t unusual for her to have episodes where she would go incommunicado over some perceived slight, this time it felt different. There wasn’t any argument or any reason that anyone could think of that she would drop off like this. Not that she always needed a reason that others could see, but things had been particularly good in the weeks leading up to this. We had plans to visit the Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings State Park, home of the celebrated author of The Yearling, and she was excited.

When we arrived at her place and knocked at her door, there was no sound other than her dog yelping at the window, frantically. As we became increasingly worried, we banged loudly to try to wake her if she was asleep, but there was no answer. As twilight slipped into darkness and the tree shadows slanted across her front door, my annoyance shifted to fear as it became less and less likely that she was simply ignoring us.

My wife suggested that we call the police, but I worried about getting them involved. After a while, I called the maintenance number for the apartment complex, and was told that the neighbors had complained about the dog barking from my mom’s place. When I told him what was happening, the maintenance man showed up quickly. He knocked and announced himself to no answer, and when I asked him if he had a key and told him that I would sign anything that I needed to in order to get that door opened, he informed me that he did not have one. He could break the door open, but that would require an expensive repair, so he decided to check the windows to see if any were unlocked. He walked around her unit, trying every window, and the very final one, the one in her bedroom above her bed that nobody wanted to have to crawl through, opened right up.

The window was about six feet off of the ground, one of those windows that are primarily for light. She probably couldn’t reach it and didn’t know that it was unlocked. Lacking a step-ladder, my brother and I boosted him up to the window. He pushed the screen into the darkened room, and carefully crawled inside. Moments later, his exasperated voice cried through the window, saying “She gone, bro!” several times through the window. “She gone.” I’ll never forget his sympathetic and urgent voice crying through my mom’s window, announcing the death of my mother. Afterwards we embraced, and he told me how sorry he was.

What happened next was a whirlwind that I won’t attempt to describe in detail. The police showed up and informed me that she had died several days beforehand in her bed and that her bedside table had numerous prescription pill bottles that they would take to investigate. I have no sense of time during the remainder of that evening, but the amount of time that it took them to look through her room seemed to me exorbitant. At one point my sister-in-law ordered us a pizza, for which I was grateful because I hadn’t felt the hunger setting in. Eventually, they allowed us to go in.

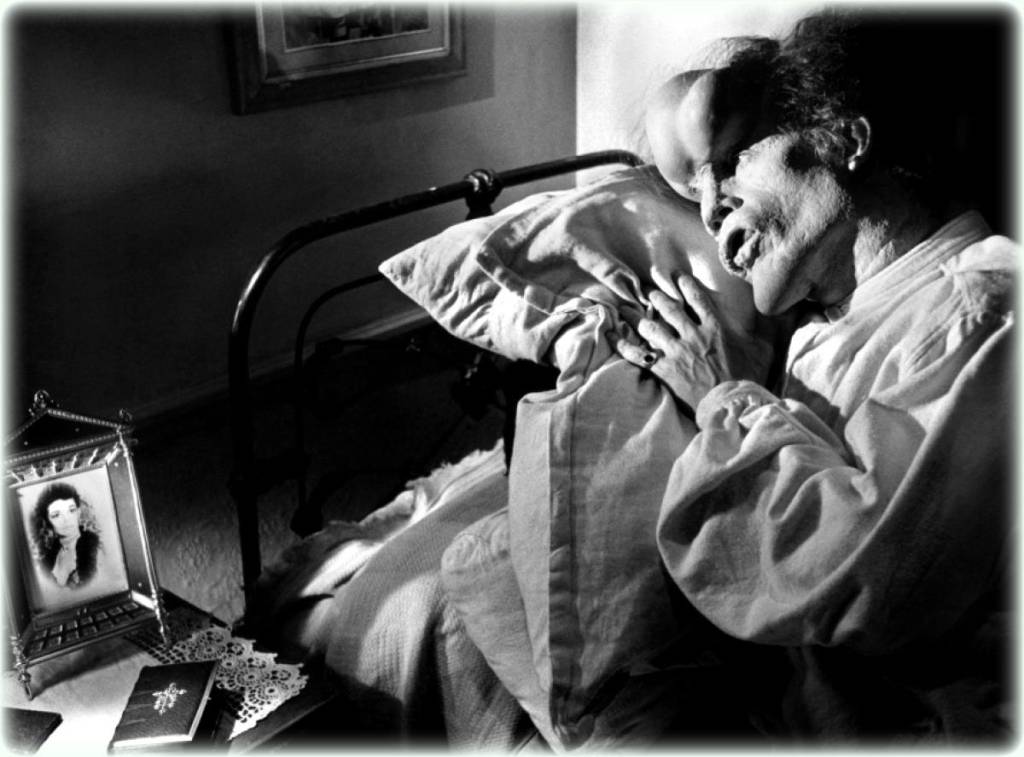

When I went into her room, she was comfortably wrapped up in her favorite comforter on her large bed. I remember that she looked peaceful. My brother sat beside her, stroked her hair, told her goodbye and that he loved her. I tried to remember the last time that I saw her and I couldn’t. I still can’t. We mostly spoke on the phone.

When someone we love dies, a tether breaks that connects us to the world. It must be repaired but it cannot. We learn to live with it. This is true regardless of how complicated our relationship was with the person who died, and anyone who knew my mother had a complicated relationship with her at best. The closer a person was to her, the more complex the relationship became until she pushed away almost anyone near her. She was brilliant (she was a wonderful writer who was, at one point, syndicated by the New York Times for a series of humorous articles about middle-class motherhood, a fact that she was very proud of), and she was constantly desperate for validation, betraying a level of self-esteem that was abyssal.

She also had a violent personality. Something was deeply wrong with her, something inside her brain was broken. She was in turns loving and compassionate, self-centered and deeply hurtful, extremely independent and wildly needy. I am not equipped to diagnose her, but she always claimed to be bi-polar. She went through several, usually court-ordered, treatment programs that occasionally seemed to help a little, but just as often caused her to come out with an ever-growing addiction to prescription medications, of which Oxycodone was only one part.

I have no way of knowing if she was ever truly suicidal, but some of my oldest memories of her involved her telling me that she was going to kill herself. My brother once had her Baker Acted because of her threats, a deeply difficult thing to have to do to a parent. When I was very young, my dad once had to end a conversation that I was having with her over the phone because I burst out crying almost as soon as we started talking. I was inconsolable. She told me that she was never going to see me again, that she was going to die soon and that I was going to be better off without her. That it was going to end her sadness, which is a good thing. I remember resenting my dad because I felt like cutting our conversation off might add to her sadness, but later I realized that he was saving me from her manipulations as best as he could. You’ll understand why the word “accidental” on the autopsy report carries a lot of weight for me.

My mom had a great talent for making me feel special in ways that nobody else could, and she could tear me down just as quickly and deeply, often in the same day. But when she was on, when her mind was balanced, she could be the most lovely, brilliant, personable, witty person to spend time with. A person who it still pains me, after all these years, to remember that I will never spend time with again.

My immediate reaction to her death was complicated. One expects pure grief in times like that, but there are other things mixed in there as well. After my initial shock, once I could feel anything beyond the horror of what had been ripped away from me, I noticed a kernel of something in my swamp of emotions that didn’t seem to belong. While I couldn’t articulate it at the time, I felt something deep within myself that I wasn’t comfortable with. Something that made me feel ashamed. I ignored it.

Months passed, and my wife, by brother, and I sat down to watch The Elephant Man, a movie about a man who should not remind me of my mother. It stars Anthony Hopkins and John Hurt, and it’s about John Merrick, a real life Englishman (whose actual name was Joseph Merrick) who was afflicted by extreme physical deformity, most likely Proteus Syndrome. Taking place in the late 1800’s, the film is less surreal and more linear than what most would associate with David Lynch, which may account for it’s immediate success both critically and commercially, a rarity among Lynch’s work.

In the film, John spent most of his life in a freak show being “managed” by a man named Mr. Bytes who proclaimed to be John’s owner. Mr. Bytes abuses John mercilessly, starving and beating him regularly. Occasionally he forces John to sleep in the monkey cage. Eventually, a London surgeon named Frederick Treves discovers John and takes him to live in the hospital where he works. When Dr. Treves first meets John, he assumes that John is mentally handicapped because he doesn’t seem to be able to speak. The rest of the film is about discovering that John not only can speak, but is quite eloquent, intelligent, and sophisticated. It is about his search to live with dignity and love in a society ill-equipped to allow someone like him to do such things.

John is a man for whom even the most basic things are exceedingly difficult. People constantly recoil in disgust at the sight of him, most want to exploit him at best and abuse him for their entertainment at worst—even the friendly Dr. Treves is somewhat guilty of using John to advance his own interests, a fact that causes him much guilt throughout the film. One of John’s great dreams is simply to be able to sleep laying down, something that is impossible for him because the deformity of his head will cause him to asphyxiate himself due to the weight of the tumors all over his skull. A picture on his wall depicts a child laying down, asleep, in bed, and John looks at it with reverence and longing. At the end of the film, after having what must have been one of the greatest days of his short life (he got to go to the theater, something he’d long dreamed of doing, and he got to do so as himself, without a mask. The lead actress dedicates her performance to him, and he receives a standing ovation), he removes the pillows that support his body and keeps him upright when sleeping, and lies down to sleep, leading to his death by asphyxiation. Supposedly it is a peaceful death.

The image of John making up his bed in order to lay down and die broke me. I’ve never cried so hard during a movie. The thought of a person dying peacefully in a bed had obvious extra weight for me so shortly after discovering my mom, but there was something else that I felt at that moment, something that I had also felt when discovering my mom and hadn’t really confronted or understood, something that gnawed at me silently, and tore at my heart: I also felt relief.

I cannot know if John laid down to sleep with the intent to die, or if he simply took his attempts to live with dignity too far after coming so far. Maybe he was tired of how much work he had to put into simply existing, maybe he wanted to end his life on a high note knowing that things could very easily get much, much worse for him. Regardless, I felt a tragic relief when his breathing slowed to a stop, knowing that he was loved, after such a perfect day, comfortably in his bed. Life, for him especially, always contained the high likelihood of things becoming more dangerous, more painful, more frightening.

Likewise, my mom’s mental and physical health constantly deteriorated, and her future looked increasingly bleak. With fewer and fewer friends and a basic inability to take care of herself, I constantly worried about what her future would look like after her diminishing resources dried up. She could hardly make ends meet in her business, so she relied on her father’s financial help, which was very finite. My brother and I didn’t have the money or space to take care of her and she would have pushed us away even if we had.

As the walls closed in around her, did she take those pills irresponsibly, knowing what was likely to happen to her? It’s impossible to say. But what I can tell you is that the last time we spoke, we made plans to go on a day trip together, and in spite of our increasingly volatile relationship, she died excited about something, comfortably, in her own home. And I felt relief that the brutality of the world couldn’t touch her anymore, and that the peace that she hopefully found there at the end, as she laid down in her plush, pillow-crowded bed, could never be taken away.

And that relief beat on my insides for months, until I watched The Elephant Man and understood it better. I wasn’t relieved because I’d avoided a burden, I was relieved that she wouldn’t have to worry anymore. As with John Merrick, I wanted her to find a way to live with dignity and love, to find a sustainable happiness in a world that wasn’t designed for her. And once they found something close to that, I was relieved that they closed the book, at least, on a happy page.

Powerful comparison. Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person